2 Collecting Data

2.1 Sampling Methods

“And I knew exactly what to do. But in a much more real sense, I had no idea what to do.” - Michael Scott

Guiding question: What makes a sample “representative”?

A sample is just a subset of your population, but not every subset is equally useful. A

Probability vs. non‑probability sampling

There are two big approaches to sampling:

- In

probability sampling , you use random mechanisms so that every member of the population has a known chance of being selected. This ensures that any differences between the sample and the population are due to random sampling error, not researcher choice, and makes it possible to quantify uncertainty in estimates. - In

non‑probability sampling , you choose participants based on convenience, volunteer responses, judgement or quotas. These methods are cheaper and often necessary for exploratory or qualitative work, but they make it hard to know whether the sample really reflects the population. Lack of a representative sample reduces the validity of conclusions and can introduce sampling bias.

Whenever you want to generalize, probability sampling is the gold standard.

Simple random sampling (SRS)

In a

Example: Suppose you want to survey 100 employees of a social media marketing company out of 1,000. You assign each employee a number from 1 to 1,000 and use a random number generator to select 100 numbers. Those employees become your sample. Because each employee had the same chance of selection, the sample is likely to be representative if the sample size is large enough.

Systematic sampling

Example: All employees of a company are listed in alphabetical order. You randomly select a starting point among the first ten names—say, the 6th person—and then select every 10th person on the list (6, 16, 26, 36, …) until you have 100 employees. This produces a sample that is easy to implement but may be risky if the list order coincides with job role or seniority.

Stratified sampling

In

Example: A company has 800 junior employees and 200 senior employees. To ensure the sample reflects the seniority balance, you sort the population into two strata and randomly select 80 junior employees and 20 senior employees. Your 100‑person sample preserves the 80/20 split of the population.

Cluster sampling

Example: A company operates offices in 10 cities across the country, each with roughly the same number of employees. To conduct an employee survey, you randomly select 3 offices and survey everyone at those offices. This cuts down on travel but only works well if the offices are similar.

Non‑probability methods

Sometimes you cannot (or choose not to) use random selection. Non‑probability methods are practical for exploratory research or hard‑to‑reach groups, but they cannot guarantee a representative sample.

Convenience sampling

A

Example: You want to learn about student support services, so after each of your classes you ask fellow students to complete a quick survey. Because you only surveyed students in your own classes, the sample is not representative of all students.

Voluntary response sampling

A

Example: You email a survey to the entire student body asking for opinions about a new campus policy. Only those who feel strongly (either for or against) are likely to respond, so the results cannot be trusted to reflect the average student’s view.

Purposive sampling

In

Example: You want to understand the experiences of disabled students using university services, so you purposefully select students with varied support needs to gather a range of perspectives. This approach is useful for qualitative insight but not for estimating population-level quantities.

Snowball sampling

Example: To study experiences of homelessness, you interview one person who agrees to participate; she introduces you to other people she knows who are also homeless. The sample grows like a snowball, but you have little control over how representative it is.

Working in JMP Pro 17

Although you won’t implement complex sampling plans in JMP, it’s helpful to know how to create random subsets for practice or model validation. To select a simple random sample from a data table, use Rows → Row Selection → Random Sample to mark a proportion or number of rows at random, then Tables → Subset to create a new table of just those rows. For stratified sampling, add a column indicating the stratum (e.g., gender) and use Row Selection → Stratify or a script to select random rows within each level. To take a cluster sample from a large data set, you can create a column identifying clusters (e.g., schools) and use Tables → Subset to extract all rows from randomly chosen clusters. While JMP has tools for convenience (e.g., sorting and taking the first \(n\) rows), remember that non‑probability sampling cannot support generalizable inference.

Recap

| Keyword | Definition |

|---|---|

| Representative sample | A sample that accurately reflects key characteristics of the population. |

| Probability sampling | Sampling technique using random selection so each unit has a known chance of inclusion. |

| Non‑probability sampling | Sampling techniques based on convenience or judgement without randomisation. |

| Simple random sampling | Every unit has an equal chance of selection; implemented via random number generators. |

| Systematic sampling | Selecting every \(k\)-th unit from an ordered list after a random start. |

| Stratified sampling | Dividing the population into subgroups and randomly sampling within each subgroup. |

| Cluster sampling | Randomly selecting entire groups (clusters) and studying all units within them. |

| Convenience sampling | Including the most accessible units; prone to sampling and selection bias. |

| Voluntary response | Sampling based on participants who choose to respond, often those with strong opinions. |

| Purposive sampling | Selecting cases based on researcher judgement of what is most informative. |

| Snowball sampling | Recruiting participants via referrals from initial subjects, often for hidden populations. |

Check your understanding

You want to estimate the average GPA of all first‑year students at your university.

- Name two probability sampling methods you could use.

- Briefly explain why a convenience sample of your friends might mislead you.

A researcher selects every 5th name from a sorted list of patients to survey. What sampling method is this? Under what circumstance might this method introduce bias?

Compare stratified sampling and cluster sampling. Give an example of a scenario where each would be appropriate.

Explain why voluntary response samples often yield extreme views and cannot be trusted for generalizing to a population.

In JMP, how could you create a simple random sample of 150 observations from a data table with 2,000 rows?

(a)Simple random sampling (assign each first‑year student a number and randomly select using a random number generator); stratified sampling (divide students by major or residence hall and sample proportionally within each group). (b) Your friends are likely from similar classes or social circles, so they may have similar study habits; they might not reflect the broader student body.

This is systematic sampling. It works well if the list has no pattern related to the outcome. If patients are sorted by appointment time, every 5th patient might always be a morning appointment, which could bias results if morning and afternoon patients differ.

Stratified sampling divides the population into meaningful groups and samples within each (e.g., sampling men and women separately when studying height). It ensures each subgroup is represented. Cluster sampling selects whole groups (e.g., choosing three hospitals at random and surveying all nurses within them) to save cost when the population is geographically spread out.

People with strong positive or negative feelings are more likely to volunteer, while those who are neutral remain silent. This self‑selection skews the sample, so the responses do not reflect the average opinion in the population.

2.2 Experimental Design

“All life is an experiment. The more experiments you make the better.” -Ralph Waldo Emerson

Guiding question: How do we design surveys and experiments?

Statistics gives us two complementary ways to gather evidence:

Principles of good experimental design

Experiments aim to isolate the effect of a treatment by controlling other sources of variation. Four key principles help us get there:

Randomization. Assigning units to conditions by chance ensures that, on average, groups are comparable on both observed and unobserved characteristics. In a

completely randomized design, every unit is assigned independently—like students randomly given different cell phone use limits in a sleep study. In arandomized block design, units are first grouped on a relevant characteristic (e.g., soil plots by rainfall zone) and then randomly assigned within each block. Randomization also applies to order of runs: in a manufacturing experiment, running treatments in random order prevents the effect of ambient conditions (e.g., temperature) from confounding with other variables.For example, in a drug study with 20 mice and two test kits (A and B), you might randomly select 10 mice to receive kit A and the remaining 10 to receive kit B. Randomization transforms systematic variation (such as age or weight differences) into random variation, preventing confounding of the treatment effect with extraneous factors.

Control and placebo. Experiments compare a

treatment group to acontrol group . The control may receive “usual care” or aplacebo to account for expectations. Placebo-controlled designs are common in medicine because participants may improve simply because they believe they’re being treated. By keeping all other conditions identical and varying only the active ingredient, the researcher can attribute differences in outcomes to the treatment itself rather than to the act of giving the treatment.Replication. Repeating the same treatment on multiple experimental units lets us estimate natural variability and distinguish real effects from random noise. For example, measuring battery life on several cells under the same charging condition gives a better estimate than using just one battery.

Blocking. If you know a nuisance factor (like soil type or patient age) affects the response, block on it. In a

block design , you divide units into homogeneous groups and then randomize treatments within each block. In biological experiments, mice are naturally grouped by litter, and chemical samples often come in batches; these natural groupings can serve as blocks. By assigning treatments randomly within each litter or batch, you control for variation due to the block (e.g., genetic or batch differences) and gain more precise estimates of the treatment effect.

A good design often combines these ideas: you might randomize fertilizer treatments within rainfall blocks and measure each plot’s yield multiple times. Designs also come in two broad structures: between‑subjects experiments, where each unit receives exactly one condition, and within‑subjects (or repeated‑measures) experiments, where each unit experiences all conditions in random order. Within‑subjects designs reduce variability but require care to avoid order effects—randomizing or counterbalancing the order of conditions is essential.

Designing unbiased survey questions

Surveys need two kinds of care: how you select respondents and how you ask questions. For representative sampling methods, see Section 2.1. Here we focus on question design. Well‑written questions are the foundation of trustworthy research. Biased or confusing wording can distort data and mislead decision‑makers. Common pitfalls include:

Leading questions: wording that nudges respondents toward a particular answer.

Biased: “Don’t you agree that our new app is much easier to use?”

Unbiased: “How would you rate the ease of use of our new app?”Loaded questions: questions that assume something controversial is true (e.g., “When did you stop wasting time on your phone?”)Double‑barreled questions: asking about two things but allowing only one answer. The respondent may have different answers for each part, so the result is uninterpretable. For example, “Do you intend to leave work and return to full‑time study this year?”—someone may be planning to leave work but not to study, or vice versa. Another example: “How would you rate our products and level of service?” Because it blends product quality with service quality, a single rating cannot reveal which aspect the respondent is judging.

Ambiguous wording: vague or multi‑interpretation phrases that lead different respondents to answer different questions. For example, a survey item that asks “How do we compare to our competitors?” leaves respondents guessing whether you mean price, quality, or customer service.

To craft unbiased survey questions:

- Use neutral language. Avoid emotionally charged words and let respondents choose their own answer.

- Be specific and clear. Define terms and make sure every respondent interprets the question the same way.

- Ask one thing at a time. Split double‑barreled questions into separate items.

- Balance response options. Provide symmetrical, evenly spaced choices (ie. 5-point Likert Scale).

- Pilot test your survey. Try it on a small group to catch confusing wording or unexpected interpretations.

These principles help respondents understand your survey and give honest answers.

Putting it all together

In practice, you often combine surveys and experiments. For example, a company might randomly assign new customers to receive one of two onboarding emails (experiment), then survey them about satisfaction. You would:

- Randomly assign customers to email A or B.

- Ensure both groups are comparable (randomization).

- Collect follow‑up satisfaction surveys using neutral, clear questions.

- Replicate across multiple cohorts and possibly block by customer type (e.g., new vs. returning).

Working in JMP Pro 17

- Randomize and block. When running experiments in JMP, create a column for treatment assignments using Col → Formula → Random to simulate random assignment. Use Tables → Sort to randomize run order, or define blocking factors as separate columns and use Fit Model to include them in your analysis.

- Control and replicate. For experiments with control and treatment conditions, use Analyze → Fit Y by X for simple comparisons or Analyze → Fit Model for multifactor designs. Replicate treatments by duplicating rows; JMP will treat these as separate experimental units.

- Design surveys. Use Rows → Row Selection → Random Sample to draw pilot samples. Store survey questions in a Data Table with labels and notes. To pilot test question wording, subset your sample and collect feedback, then refine the wording before launching the full survey.

Recap

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Random assignment | Assigning sampled units to treatment conditions by chance to create comparable groups. |

| Treatment group / control group | Groups receiving the experimental intervention and baseline comparison, respectively. |

| Placebo | An inert treatment used to mimic the experience of the intervention to control for expectations. |

| Replication | Repeating the same treatment on multiple experimental units to estimate variability. |

| Blocking | Grouping similar units and randomizing within each group to control a nuisance factor. |

| Between‑subjects design | Each unit experiences only one condition; comparisons are across subjects. |

| Within‑subjects design | Each unit experiences all conditions in random order. |

| Leading question | A survey question that suggests a particular answer. |

| Loaded question | A survey question containing an assumption or implication. |

| Double‑barreled question | A single question that asks about two things. |

| Ambiguous wording | Vague terms that can be interpreted differently by different respondents. |

Check your understanding

- Explain the difference between random sampling and random assignment. Why are both important, and in what contexts do they apply?

- Name the four principles of good experimental design and give a brief example of each.

- Consider this survey question: “How satisfied are you with the cost and quality of your textbooks?” Identify the problem and rewrite the question.

- In a study of exam performance, 60 students volunteer for tutoring and 60 do not. The volunteer group has a higher average GPA than the non‑volunteer group. Explain why this study may not show that tutoring causes better performance. How could you redesign it?

Random sampling determines who gets into the study. Every member of the population has a known chance of selection, improving generalizability. Random assignment determines which condition participants experience, creating comparable groups and allowing causal conclusions. Surveys rely on random sampling; experiments rely on random assignment.

Randomization: assign units by chance (e.g., randomize phone use levels to study sleep). Control/placebo: include a baseline or placebo condition to isolate the treatment effect. Replication: repeat treatments on multiple units, like testing several batteries under the same condition. Blocking: group units by a nuisance factor (e.g., soil type) and randomize within blocks.

The question is double‑barreled—it asks about cost and quality. Rewrite as two separate questions (e.g., “How satisfied are you with the cost of your textbooks?” and “How satisfied are you with the quality of your textbooks?”).

Volunteers may differ systematically from non‑volunteers (e.g., motivation or prior GPA). Random assignment is missing. To infer causality, randomly assign students to tutoring or control groups and compare outcomes, possibly blocking on prior GPA.

2.3 Observational Studies vs. Experiments

“You can observe a lot by just watching.” - Yogi Berra

Guiding question: Why are observational studies sometimes problematic for conclusions?

At first glance, collecting data looks the same whether you’re watching what happens or deliberately changing something. But how you gather the data matters tremendously for what you can conclude.

Observational studies: watching without intervening

In an

Cohort studies , where a group of people linked by a characteristic (e.g., birth year) is followed over time. Researchers compare outcomes between those exposed to some factor and those not exposed.A classic example of a cohort study is the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), which has been described in detail in the International Journal of Epidemiology. In 1948 the National Heart Institute recruited a community‑based cohort of 5,209 adults aged 30–59 years from Framingham, Massachusetts, to investigate causes of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Two of every three families in the town were randomly sampled and invited; 4,494 (about 69%) agreed to participate, and an additional 715 volunteers joined. This initial prospective cohort has been followed every two to four years with detailed medical histories, physical examinations, electrocardiograms and laboratory tests. By following participants longitudinally for decades, the FHS identified major risk factors for CVD—such as high blood pressure, cholesterol, and smoking—helping to shape modern cardiovascular prevention guidelines.

Case–control studies , where people with a condition (“cases”) are compared to similar people without it (“controls”) to look for differences in past exposures.For example, a German study1 compared 118 patients with a rare form of eye cancer called uveal melanoma to 475 healthy patients who did not have this eye cancer. The patients’ cell phone use was measured using a questionnaire. On average, the eye cancer patients used cell phones more often. The cases were those who had developed uveal melanoma and the controls were those who did not uveal melanoma. The cell phone use was compared between the two groups.

Because participants choose their own behaviors, observational data reflect the real world and are often the only ethical way to study harmful exposures. For example, you can’t ethically assign people to smoke or not smoke, so the long‑term effects of smoking are studied by tracking smokers and non‑smokers over time.

Observational studies are usually quicker and cheaper than experiments and have high ecological validity (they mirror everyday life). But they have a critical limitation: you can’t be sure whether differences in outcomes are caused by the exposure or by other factors that differ between groups. For example, a highly publicized 1985 study from Johns Hopkins University linked coffee consumption to an increased risk of heart disease, especially for heavy drinkers. The study’s findings, published in the American Journal of Epidemiology, were later challenged by other research that pointed out the failure to adequately control for the effect of cigarette smoking. Once smoking was controlled for, the link between coffee consumption and increased risk of heart diseas was no longer significant.

Experiments: deliberately changing something

In an

Experiments also offer a controlled environment, making it easier to isolate the effect of a single factor. However, they can be expensive, time-consuming, or unethical to conduct.

For example, suppose we were interested in the association between eye cancer and smart phone use. Suppse we conduct an experiment, such as the following:

- Pick half the students from your school at random and tell them to use a smart phone each day for the next 50 years.

- Tell the other half of the student body not to ever use smart phones.

- Fifty years from now, analyze whether cancer was more common for those who used smart phones.

There are obvious difficulties with such an experiment:

It’s not

ethical for a study to expose over a long period of time some of the subjects to something (such as smart phone radiation) that we suspect may be harmful.It’s difficult in practice to make sure that the subjects

behave as told. How can you monitor them to ensure that they adhere to their treatment assignment over the 50-year experimental period?Who wants to

wait 50 years to get an answer?

Thus, an observational study would be preferred over an experiment.

Why observational studies can mislead

Observational data are susceptible to

Randomization is the only method that can eliminate potential confounders by balancing both measured and unmeasured factors across treatment groups. In observational research, statistical methods like stratification, regression adjustment and propensity score matching can reduce bias, but they depend on untestable assumptions: all confounders must be measured correctly and modeled properly. Many important confounders may be unknown or infeasible to measure. Even meticulously controlled observational studies cannot remove all confounding. As a result, observational evidence alone “cannot support conclusions of

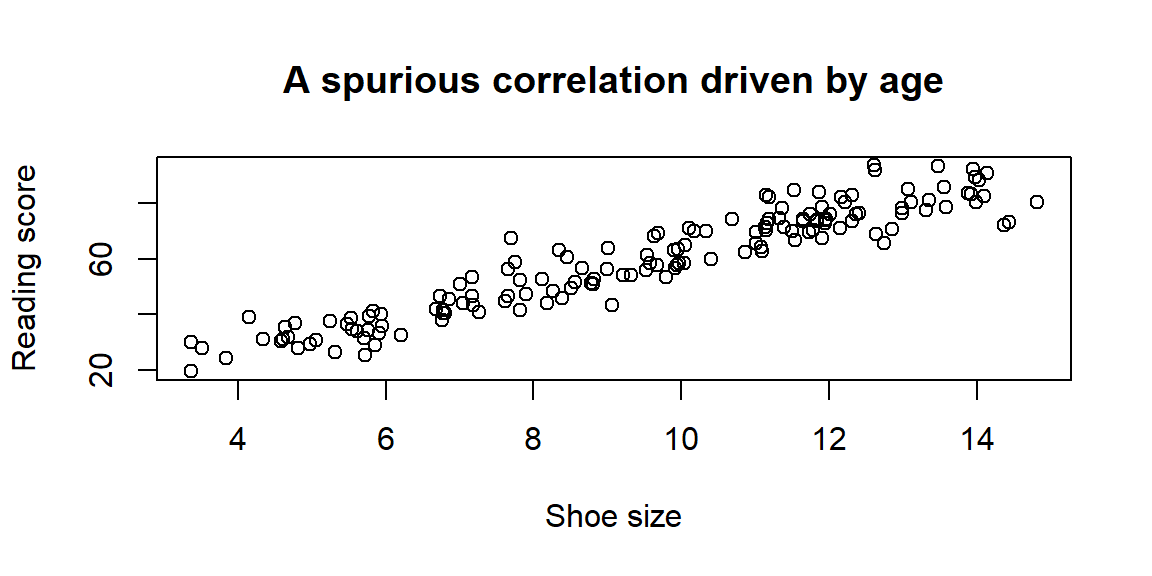

Below is a simple simulation illustrating confounding. Shoe size and reading ability appear positively related, but both are driven by age. When age is not controlled, a misleading association emerges.

The scatterplot shows a strong correlation between shoe size and reading, even though neither directly affects the other. The common cause is age. Observational studies must always consider whether a hidden variable like age could be responsible for an observed association.

Working with observational data in JMP Pro 17

In JMP you can explore observational data using Graph → Graph Builder or Analyze → Fit Y by X to visualize associations. Use Analyze → Fit Model for regression or ANOVA, including potential confounders as predictors. JMP will happily fit a model and produce p-values, but you must interpret the results cautiously. Remember:

- Including covariates can adjust for measured confounders, but unmeasured confounders remain.

- Associations observed in scatterplots or regression analyses do not imply causation.

- Use notes and metadata fields to document the study design—observational or experimental—and any potential sources of bias.

Recap

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Observational study | A study in which researchers record exposures and outcomes without assigning treatments or interventions. |

| Cohort study | Observational design where a group is followed over time to compare outcomes between exposed and unexposed members. |

| Case–control study | Observational design where people with a condition (“cases”) are compared to similar people without the condition (“controls”) to look for differences in past exposures. |

| Experiment | A study where researchers introduce an intervention and randomly assign subjects to treatment or control groups. |

| Confounding | A situation where a third factor influences both the exposure and the outcome, potentially creating a spurious association. |

Check your understanding

A nutrition researcher recruits people who already take daily multivitamins and compares their health outcomes to people who do not.

- Is this an observational study or an experiment?

- Name at least two potential confounding variables.

In a randomized trial, half the participants are assigned to eat a Mediterranean diet and half to continue their usual diet. After a year, the first group shows lower cholesterol. Explain why randomization strengthens the causal interpretation.

A cohort study finds that people who bike to work have lower rates of depression than those who drive. Suggest two reasons why this association may not reflect a causal effect of biking.

Describe a research question that would be unethical or impractical to answer via experiment but could be studied observationally. Explain why.

a)This is an observational study because participants choose whether or not to take multivitamins. b) Potential confounders include diet quality, exercise habits, socioeconomic status, access to healthcare, smoking status and other health behaviors.

Randomization assigns diets by chance, so, on average, both known and unknown factors (age, lifestyle, genetics) are balanced across the groups. Therefore, differences in cholesterol are likely due to the diet rather than pre‑existing differences.

People who bike may have higher baseline fitness and better mental health; they might live in neighborhoods with better infrastructure or community support; they may also have lifestyles that promote well‑being (e.g., more time outdoors). Any of these confounders could explain the observed association.

Studying the long‑term effects of smoking is unethical to do experimentally, because you can’t randomly assign people to smoke. Instead, researchers observe smokers and non‑smokers and compare outcomes.

2.4 Sources of Bias

“Normally if given a choice between doing something and nothing, I’d choose to do nothing. But I would do something if it helps someone do nothing. I’d work all night if it meant nothing got done.” - Ron Swanson

Guiding question: How can bias creep into data collection?

When we talk about bias in statistics, we mean a

How bias differs from sampling error

Whenever we select a sample, the numbers we compute (like the mean or proportion) will vary from one sample to the next. This variability is called

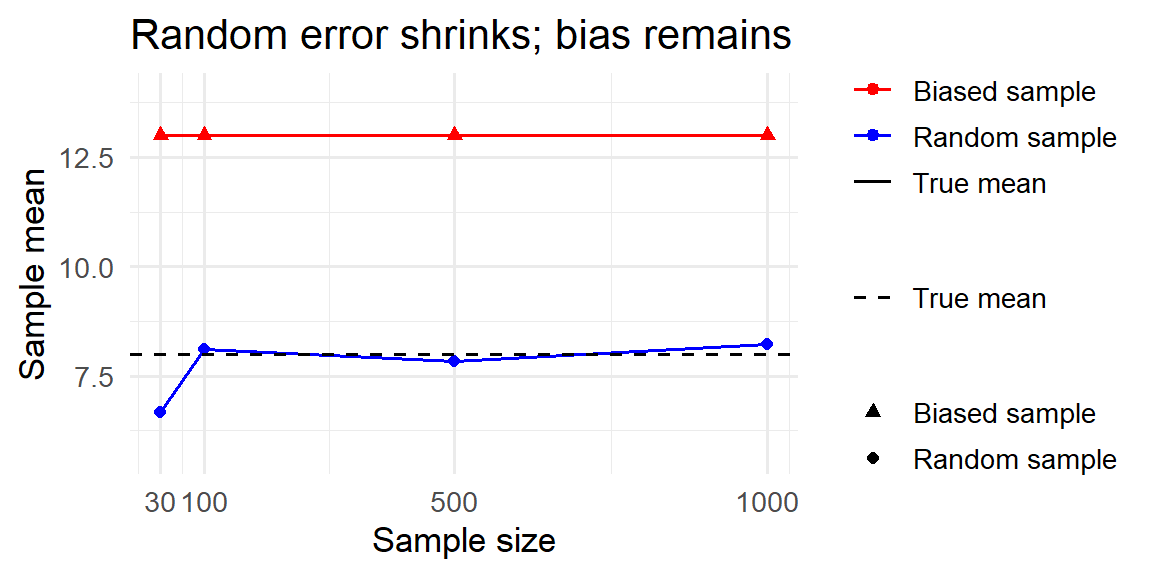

To illustrate the difference, imagine a population with a true average income of $8 (in arbitrary units), made up of 70% low earners (income of 5) and 30% high earners (income of 15). Below we simulate two ways of sampling from this population: a fair simple random sample and a biased sample that over‑selects high earners (80% high, 20% low). As the sample size grows, the random sample mean settles near the true average, while the biased sample mean stays high. This shows that increasing the sample size reduces random error but does not fix bias.

Common sources of bias

Bias can enter at many points in the data‑collection process. Here are some of the most common culprits:

- Coverage (undercoverage) bias. A

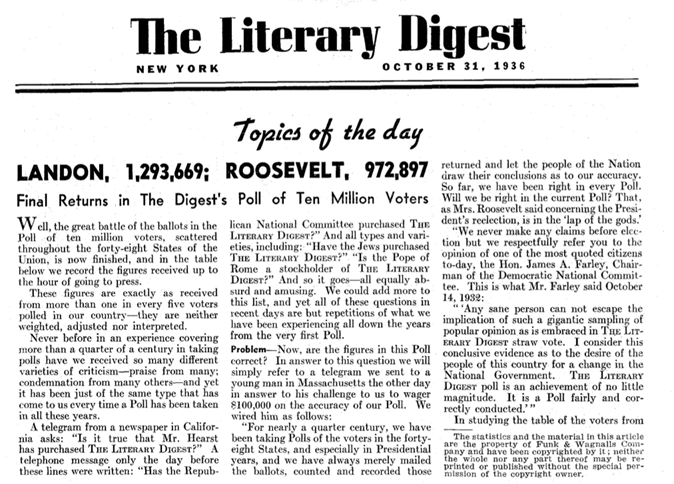

coverage bias occurs when some members of the population are not included in the sampling frame. The Literary Digest’s famous 1936 presidential poll relied on telephone directories and car registration lists, thereby missing less affluent voters who tended to support Franklin Roosevelt. Because those voters were excluded, the sample favored wealthier respondents and overpredicted Alfred Landon’s support.

Nonresponse bias. A

nonresponse bias arises when selected individuals choose not to participate and the responders differ systematically from nonresponders. In the same 1936 survey only 25 % of those sampled returned the mail‑in ballot. Landon supporters were more likely to return the survey, so the results overestimated his popularity.Voluntary response bias. When people opt into a survey on their own—like call‑in radio polls about controversial topics—the sample disproportionately includes individuals with strong opinions. This

voluntary response bias can produce extreme results because moderate voices remain silent.Convenience sampling bias. A

convenience sample chooses whoever is easiest to reach. If you stand outside a gym to survey “all adults in the city,” your sample will overrepresent health‑conscious people. Convenience sampling often leads to coverage problems.Response (measurement) bias. Even if we select the right people, the way we ask questions or record data can introduce

response bias . Response bias occurs when the measurement process influences the answer: leading questions or unbalanced answer choices can nudge respondents toward particular responses.Social desirability bias occurs when people underreport socially undesirable behaviors or overreport virtuous ones.Survivorship bias. When we only observe “survivors” and ignore those that dropped out or failed, we can mistake success for the rule.

The most famous example of this is the WWII bomber problem. During WWII, analysts tallied bullet holes on returning Allied bombers and saw clusters on wings and fuselage, with relatively few in engines and cockpit. The intuitive fix was to add armor where the holes were densest. Statistician Abraham Wald pointed out the trap: these data come only from planes that survived. Holes on the survivors mark places a plane can be hit and still make it home. The missing planes—those that didn’t return—are precisely the ones likely hit in the “clean” areas (e.g., engines). So Wald recommended reinforcing the areas with the fewest holes on the survivors, not the most. That’s survivorship bias: drawing conclusions from only the observed “winners” and ignoring the unseen “failures.”

Recall bias. In retrospective studies, participants may not remember past events accurately. People who have developed an illness might recall exposures differently than healthy controls, leading to systematic differences.

Interviewer bias. The interviewer’s tone, appearance or expectations can subtly influence responses. Neutral wording and training can reduce this effect.

Healthy‑user bias and attrition bias. People who choose to participate in certain programs or who remain in a study for its duration often differ from those who do not, leading to biased estimates.

Each of these biases stems from the way participants are chosen or how data are measured; they cannot be “averaged out” by larger samples.

Mitigating bias

To minimize bias:

- Use probability sampling whenever you want to generalize to a population. Random sampling helps guard against undercoverage and voluntary response bias.

- Ensure your sampling frame matches your target population. Consider oversampling underrepresented groups and weighting responses to reflect their true proportion.

- Follow up with nonresponders and offer multiple modes of participation to reduce nonresponse bias.

- Design neutral, balanced questions and offer anonymity to reduce measurement and social desirability bias.

- Document who was invited and who actually participated so you can assess potential biases.

- In observational studies, adjust for measured differences between participants and nonparticipants using weighting or modeling; but remember that unmeasured biases may remain.

Working in JMP Pro 17

JMP cannot magically remove bias, but it can help you detect and address it:

- Explore representativeness. Use Distribution and Graph Builder to compare your sample’s demographics to known population benchmarks. If certain groups are underrepresented, consider weighting or stratified analysis.

- Identify nonresponse patterns. Create an indicator column for nonresponders and use Fit Y by X or Fit Model to see whether response differs by variables like age or region.

- Design balanced surveys. Although JMP does not build surveys, you can use scripts or formulas to randomize question order, generate balanced answer scales, and check for item nonresponse.

- Apply weights. If you oversample some groups, add a weight column and specify it in analyses (under the red triangle menu) so that estimates reflect the target population.

Recap

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Coverage bias | Systematic error that arises when part of the population is missing from the sampling frame. |

| Nonresponse bias | Bias introduced when individuals who do not respond differ meaningfully from those who do respond. |

| Voluntary response bias | Bias caused by allowing people to opt into a survey; respondents with strong opinions dominate the sample. |

| Response bias | Bias that arises from flaws in the measurement process, such as leading questions or social desirability. |

| Sampling error | Natural variability in statistics from sample to sample; decreases with larger samples. |

| Bias | Systematic error due to design or measurement; does not diminish with larger samples. |

| Survivorship bias | Focusing only on observed “survivors” and ignoring those that failed, leading to overly optimistic conclusions. |

Check your understanding

A tech company sends an email survey to customers using its premium service. Over half of the recipients do not respond. The company concludes that 85 % of its customers are satisfied.

- Identify two potential sources of bias.

- Suggest one way to mitigate each bias.

- Identify two potential sources of bias.

A political action group hosts an online poll on its website asking visitors whether they support a proposed tax increase. Seventy‑five percent say “no.” What type of bias is most likely, and why does this poll not reflect general public opinion?

Suppose you draw a simple random sample of 1,000 Baylor students from a roster and send them a questionnaire. Only 200 students respond. How could you use follow‑ups or weighting to reduce bias? Explain your reasoning.

Explain the difference between sampling error and bias in your own words. Why can a huge sample still give a wrong answer?

(a)Coverage bias and nonresponse bias. The company sampled only premium users (ignoring basic or free users) and most of the sampled customers did not respond, so respondents may differ from nonrespondents. (b) To reduce coverage bias, draw a sample from all customers or weight responses to reflect the full user base. To reduce nonresponse bias, send reminders, offer incentives or provide alternative modes (e.g., phone, mail).

This is voluntary response bias: only visitors who care enough to vote participate, and they may have strong opinions. A poll embedded on a partisan website cannot be generalized because participants are self‑selected and not representative of the broader population.

The low response rate introduces nonresponse bias. You could send follow‑up reminders, offer incentives, or contact nonrespondents by phone to increase participation. If demographic data are available for all sampled students, you can apply weights so that the 200 responders reflect the distribution of the 1,000 sampled students (and thus the target population).

Sampling error is the random fluctuation you see from one sample to the next; it decreases with larger samples. Bias is a systematic error built into the design or measurement; it doesn’t shrink with bigger samples. A huge convenience or volunteer sample can still give a wrong answer if it systematically excludes part of the population or asks questions in a biased way.

Stang, A., Anastassiou, G., Ahrens, W., Bromen, K., Bornfeld, N., & Jöckel, K. H. (2001). The possible role of radio frequency radiation in the development of uveal melanoma. Epidemiology, 7-12.↩︎